| ||

2026 Sistema Cheve

|

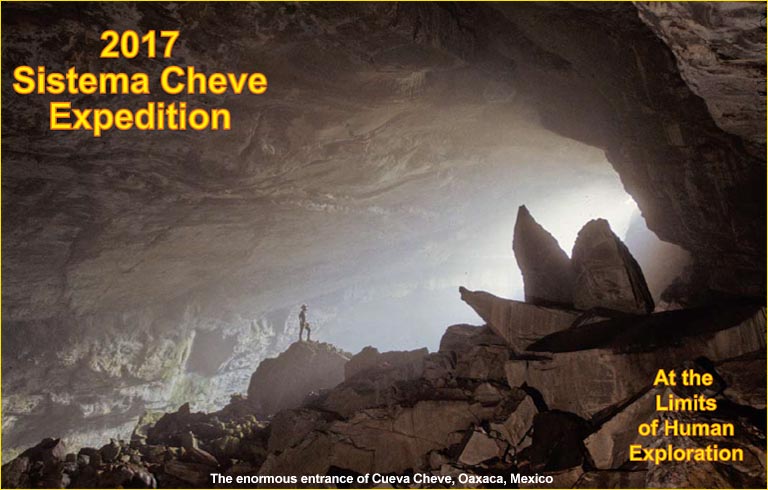

2017 Sistema Cheve Expedition

Read the expedition executive summary here. Background (en Español) In 1987 Cueva Cheve was first discovered by modern explorers at high elevation in the Sierra Juárez of northeastern Oaxaca, México. It is presently 1,484 meters deep and is the second deepest known cavern in the Western Hemisphere and the world's 12th deepest. The present limit of exploration in Cheve - at 10 kilometers from the nearest entrance - represents one of the most remote locations ever attained inside any cave on Earth. The logistics of reaching this point are enormous: more than 3 kilometers of rope need to be rigged; three underground camps established; and diving equipment for a team of four needs to be transported to the -1,362 meter level where a series of two underwater tunnels (known as sumps) begins. The final depth was achieved during a 3-month U.S.-led expedition in 2003 that succeeded in placing a four-person dive team beyond two flooded tunnels (140 and 280 meters length, respectively). The dives were highly successful and the team rapidly explored an additional 1.3 kilometers of new terrain leading deeper into the mountain. The effort was ultimately halted by an ancient tunnel collapse that blocked the route forward.

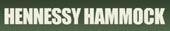

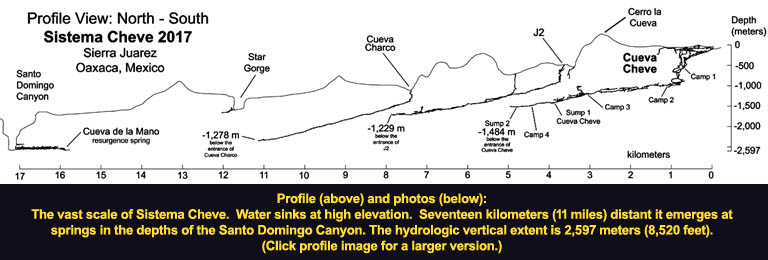

The Challenge No one has since returned to Cueva Cheve and the mystery of what remains to be discovered inside the Sierra Juárez endures. The 2003 dive team made one other important discovery: the existence of three large waterfalls that enter the cave along the stream passage between the two sumps. One of these is more than 60 meters in height and crashes into an 80- meter-long lake. There was no time to investigate these waterfalls in 2003 as the discovery of the way through Sump 1 and the river canyon beyond occurred late in the expedition. The presence of these waterfalls is significant. Sistema Cheve is known, through 3D mapping, to have been formed on at least three different levels as the subterranean river cut down through various stratigraphic layers over the course of millions of years. The active river today is the lowest level. But throughout most of the cave there exist "fossil" (old, dry) tunnels of gigantic proportions some 70 to 100 meters above the river. Because Sistema Cheve is highly fault-controlled - that is, it tends to follow large-scale cracks in the limestone strata created when the Sierra Juárez was pushed up from the Gulf of Mexico - these upper-level passages tend to lie directly above the river passage. A waterfall, then, is a "geologic drill," which creates an access path between layers. Twelve members of the 2017 team are cross-trained as divers and aid climbers. A 65-person international team from 11 countries will stage equipment to Sump 1 during the first month of the expedition. Then three successive teams of four persons will commence the exploration of what lies beyond in what will surely be one of the most remote and exciting original exploration projects of this decade. The Mission The expedition will stage out of Austin, Texas the first week of February of 2017 and will be in the field for three months. The primary objective of the expedition in March 2017 will be to establish subterranean Camp 4 in the air-filled tunnels beyond Sump 1 in Cueva Cheve, and extend exploration toward the hypothesized central trunk corridor inside the Sierra Juárez by means of aid climbing up three waterfalls that exist between Sumps 1 and 2. Should this effort be successful the effort in April and May will focus on extending exploration of the trunk tunnel north towards Cueva de la Mano. A connection between Cueva Cheve and Cueva de la Mano would produce a 2,597 meter-deep cave and would represent the deepest natural abyss yet discovered.

The current limit of exploration in Cueva Cheve represents totally unknown territory. The above map shows the surface topography (in plan view) together with the known major cave systems of the Sierra Juárez. What is known was obtained through difficult exploration and mapping during 17 expeditions over 25 years' time.The distance actually traveled underground can be three or more times the straight-line surface distance. It is approximately 10 kilometers of underground travel from the entrance of Cueva Cheve to the present limit of exploration. This is well beyond the limits of human endurance. To deal with this we break the journey into segments that represent 8 to 12 hours one-way travel time with a heavy backpack and establish underground camps at those locations. There are currently three such camps in Cueva Cheve, with the most remote (Camp 3, first set in 1990) being at the -1,100-meter level, three days from the entrance. The primary objective in 2017 will be to establish subterranean Camp 4 beyond Sump 1, to scale the waterfalls leading upwards, and, hopefully, to re-acquire the large high-level dry passage last seen just north of Camp 3. If successful it will be our further objective not only to explore this overhead tunnel deeper into the mountain, but also to connect it to dry (air-filled) cave upstream of Sump 1, thus bypassing the need for diving and allowing for all team members to participate in deeper explorations. A breakthrough of this nature could lead to rapid extension of the main cave - Cueva Cheve - to depths in excess of 2,000 meters as well as seeing the possible linkage of other large cave systems. We are expecting that the teams sent to Camp 4 will see continuous underground stays of 30 days or longer before cycling out with replacement teams. The duration of the expedition is designed to allow three independent pushes from Camp 4 by 4-person diving/climbing teams. The remainder of the 65-person support team will be staged at various camps throughout the cave to transport food and materiel to Sump 1 in support of the climbing effort beyond Sump 1. We are optimistic regarding our chances for success. The team is extraordinarily experienced, and represents the best expeditionary cave explorers from 11 nations. New Technology for 2017 A close collaboration with expedition sponsors Poseidon Diving Systems (Sweden) and SANTI have equipped the expedition with truly state-of-the-art life-support technology and environmental suits to allow underground pushes of up to 30 days and through completely water-filled tunnels. New advances in climbing technology will allow the lead team to scale previously inaccessible waterfalls to high-level dry tunnels.

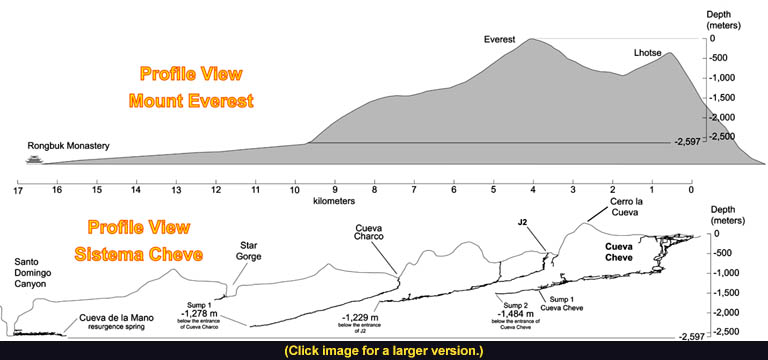

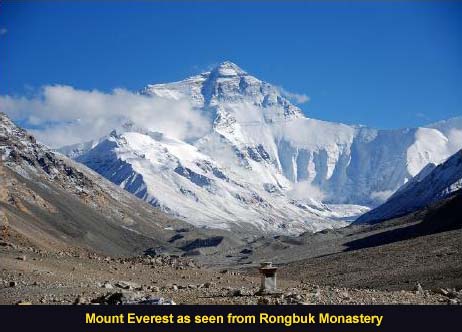

Caves are dark. You cannot see them from the surface. Their entrance often bears no portent of what is below. There is no sense of scale that can be grasped from the surface. Conversely, high-altitude mountains carry the opposite visual effect: the closer you get the more powerful the sense of scale and awe becomes. No place conveys this sense of humility better than Mount Everest. From Rongbuk Monastery (far left in the upper profile; and the point of view of the photo at left) Everest is still iconic at 20 kilometers' range. As you approach on the original Mallory route (the left ridge line in the photo) it finally becomes clear how staggeringly big this mountain is to anyone attempting to climb it. The above map shows the known extents of the Cheve cave system compared with a vertical cross section of Everest. The vast cave system dwarfs Everest in horizontal extent, extending from Lhotse to Rongbuk. The 2017 team, if successful, will travel significantly farther underground than the distance from Rongbuk Monastery to the summit of Everest with a vertical descent below the surface rivaling the elevation gain to the summit from Rongbuk glacier. Unlike mountaineers, however, the hard part begins when you have to leave - the only way out is up. A gallery of images from the 2017 Sistema Cheve Expedition can be viewed here. | |

| Copyright © 2026 U.S. Deep

Caving Team, Inc. All rights reserved. Todo el contenido tiene derechos de autor del U.S. Deep Caving Team. Todos los derechos reservados. No portion of these pages may be used for any reason without prior written authorization. | ||

Logistics

Logistics

Relative Scale

Relative Scale