| |

2026 Sistema Cheve |

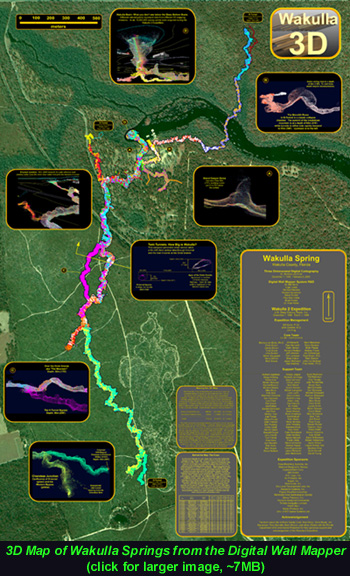

1998 Wakulla 2 Expedition

The concept has been around for a long time in the dry caving community: wouldn't it be nice to walk through an unexplored passage with a Star Trek-like scanner and later be able to tour what you had mapped in exquisite detail on your computer screen in the dry comfort of your home. Anyone who has spent any significant time surveying under a pounding waterfall, swimming through underground lakes, or crawling through mud-filled tubes eventually has this vision. The reality of cave surveying today is that you end up with, at best, a line plot and field sketch, with a great deal of artistic imagination being added to bring life to the map. This lack of precision persists, in air-filled caves, despite having the luxury of looking around, taking extra measurements, and actually sketching plan, profile, and cross-section views of the passage while still underground. The situation is even worse for cave divers. The limitations of life support equipment (even rebreathers) and, more importantly, the desire to reduce decompression when exploring in very deep flooded caves and springs, don't permit time for a relaxed look around and a thoughtful, detailed sketch of the surroundings. Everything happens fast... usually at about 1.3 meters per second - the speed of the underwater propulsion vehicle being used to get you to the limit of exploration. There is yet another problem with subaquatic speleocartography: you might not even be able to see the walls, floor, nor ceilings, due to reduced visibility. During high water conditions in north Florida tea-colored tannic water flows into the sinkholes and floods into springs reducing visibility in the underlying channelized aquifers to near zero. Sometimes the caves stay "tannic" for months. It was with that in mind that Paul DeLoach, one of the leading cave divers in the U.S. throughout the 1980s, mused during the fall of 1990 that of all the gadgets he wished he could have, "Tannic Vision" was the highest on the list. He, John Zumrick and Bill Stone were standing at the edge of Whiskey Still sink at the time. Peering down into that 50 meter deep shaft of brownish-black liquid, Paul's concept was easy to grasp: an electronic mask that somehow scanned the tunnel ahead of you, even though zeroed out with tannic acid, and projected a computer-generated mesh ahead of the mask that represented the boundaries of the underwater tunnel as it led off into the unknown. And while you are at it, why not store the data as well so you would not be bothered with having to survey -- since survey time just meant more decompression. Well, what cave diver wouldn't want one of those? Thus began the development of the Digital Wall Mapper, and preparations for the Wakulla 2 Expedition. |

| Copyright © 2025 U.S. Deep

Caving Team, Inc. All rights reserved. Todo el contenido tiene derechos de autor del U.S. Deep Caving Team. Todos los derechos reservados. No portion of these pages may be used for any reason without prior written authorization. | |